Retold by Cathleen “Cathi” Rose Manuel

Early Indigenous weddings were not nuptials by the modern definition. The principle concept to wed celebrated an adjoining of families. When an individual saw and was smitten by a member of a neighboring clan out gathering food or on a hunt, there was a lengthy process they had to endure before they married. Like modern admirers, they had to strategize challenges and overcome obstacles. Clans did not speak the same language, but courtesy is universal. Political and social conflicts may have slowed their courtship, they had to be careful. Once the pair grew comfortable with their intentions, they established communication. They exchanged dialects, established boundaries, shared values, became friends, and built a bond. They learned each other’s ways, words, and were ready to make their friendship known. They discussed their situation with their family leaders. If their family approved, then they arranged to invite the friend to their community and meet them.

The friend was an honored guest. If the family accepted them, they sent gifts back for the friend’s clan. If the gifts were received, an invitation was remitted by a return gift or service. A visit was not a date; visits spanned over days and nights; some lasted many seasons. The visits were tests that got harder and more demanding. The two friends had to learn protocols, dialect, and distinguish faces. Their friendship was tested to see if it could advance toward a relationship. If the couple became serious and their families got along, the decision to marry was their alone. This was a point to proceed to the most important step, or to part ways permanently. If they felt respect, devotion, security, trust, and commitment to a unified future, they had officially fallen in love.

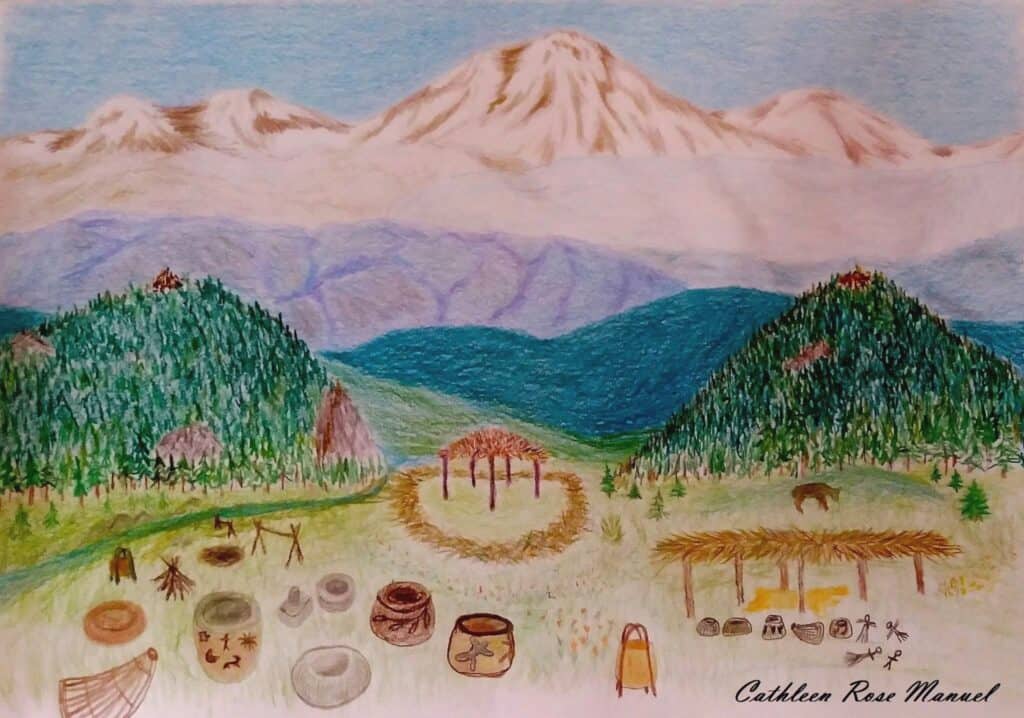

The process took time due to their differences and unfamiliarity, balance needed maintenance. Should children be in their future, their health and wealth was established before conception. Spiritual leaders were consulted before the announcements were made. Once approval and agreement was achieved, their plans for a Unity Ceremony began. This took time due to the seasons’ harvests. Older, wealthier families were required to show gratitude with valuable gifts in the forms of the best game, elaborate baskets and bowls, large lodges, and toys for the children. Material was collected from both homelands. Wealthy families had to protect their status. If their loved one’s chosen partner was poor but showed ambition and passed their tests, they were regarded as kin. Doubts, disputes, and questions of character or intent needed to be known before the Unity Ceremony ensued.

The Unity Ceremony was not a daylong event; it consisted of several days. the location was determined by its convenience for each clan’s travel distance. A council, made up of the oldest members and medicine people who represented both families, helped the couple with the decisions and conducted the ceremony. The best hunters and fishers provided the meats and pelts. The artists created gifts for everyone, dolls and small weapons were made for the children, and furs were rendered soft for the elders. Two arbors were built; one for the ceremony and one for the gift feast. Camps were set up on two hills closest to the ceremony grounds. The families separated to their camps for preparation. At dawn on the day of the ceremony, the camp closest to the east started to sing their wedding song when they descended the hill. The other camp waited until they heard the song, then they joined in and began their descent. This procedure was based on the spiritual belief that real adoration and respect is carried on frinedly wind to one’s beloved no matter how far away they are. They could be miles apart but hear their voices call. Ancestors believed that spiritual bonds could transcend the distance of death.

When the two parties arrived at the ceremony grounds, they entered into the arbor together. The families mixed and sat in a circle. This signified there were no differences between them, the gifts and duties were shared, and their lands were sovereign under their agreement. The families prayed, sang, and danced together for days. The cooks fed everyone. Nobody left without a gift. After the ceremony was done. The guests returned to their homelands and did not regard their neighbors as strangers anymore. Their family laws established protection, responsibility for raising the children, the lands’ sources were shared, communication opened, and they would be honest to one another.

Over the generations, languages mixed, songs, dances, and stories were similar but never the same as in other clans. A wedding was not material-oriented or singular. When time progressed, the concept of love was contaminated by distorted emotions and impulses, bonds were broken, families split apart, and feuds took roots and spread bitterness. When separation and disputes went unresolved, the strength and beauty of the Unity Ceremony diminished. It is a memory, but not a myth or legend. Descendants who attended the Unity Ceremonies made the old stone bowls and artifacts that were/are unearthed centuries later. Their spirits never forgot.

This story returned to heal and restore bonds that are neglected but not broken.