Breath of Life 2016: Bringing Story Back Home

By Vincent Medina

Not too long ago, a friend of mine broke a beautiful abalone necklace. The beads were scattered, the pieces fragmented, a pattern barely in place on one end of the string. Instead of buying a new necklace, she decided to put it back together and fix it. She found the existing pattern that was there, and threaded the beads and abalone together, but soon realized some pieces were missing. But it was okay. “This is what we have to work with. Some things are missing, but it can still be beautiful,” she said with a smile. And after a little work, the necklace was put together again. It will never be the same as it was before, but it was recognizable. It was beautiful.

This beautiful necklace, and my friend’s reaction resonated deeply with me. And I thought of this necklace while at Breath of Life, hosted by the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival (AICLS), just this last week on June 13th to 18th. For those unaware about Breath of Life, it is a biennial program at the University of California, Berkeley. The program’s primary objective is to connect California Indian people to the language archives of our tribal communities, while also educating participants with discusses on successful methods for language reclamation, crash courses on linguistics, understanding orthographies and writing systems, and much more. We generally team with a linguist, who helps answer practical questions on linguistic methods. At the end of the program, we present a final project on what we’ve learned and worked on.

It seems straightforward enough, but for those who attend it is a roller coaster of a week. Some were young folks speaking words they’ve never heard before but have long dreamed of speaking their languages, and some were elders reconnecting with words that were taken from them in the boarding schools. Everyone was at a different level, and had different ways of learning their language; but, we all shared our guiding force: connecting with our Indian languages. Connecting with our ancestors. Making things right for them, and for the generations yet to come.

As for me, my situation is a little different. I am a Breath of Life alum, I guess you can call me, attending three times now and understanding the immense and incredible benefits of this program. I also sit on the Board of the Advocates, so I helped with Board duties, and “behind the scenes” to try to make things flow smoothly, while still being a participant. Breath of Life is also held in the homeland of my Chochenyo Ohlone community, so there’s a special feeling to welcome so many good people to mak-ruwwatka, our home, mak-piretka, our land.

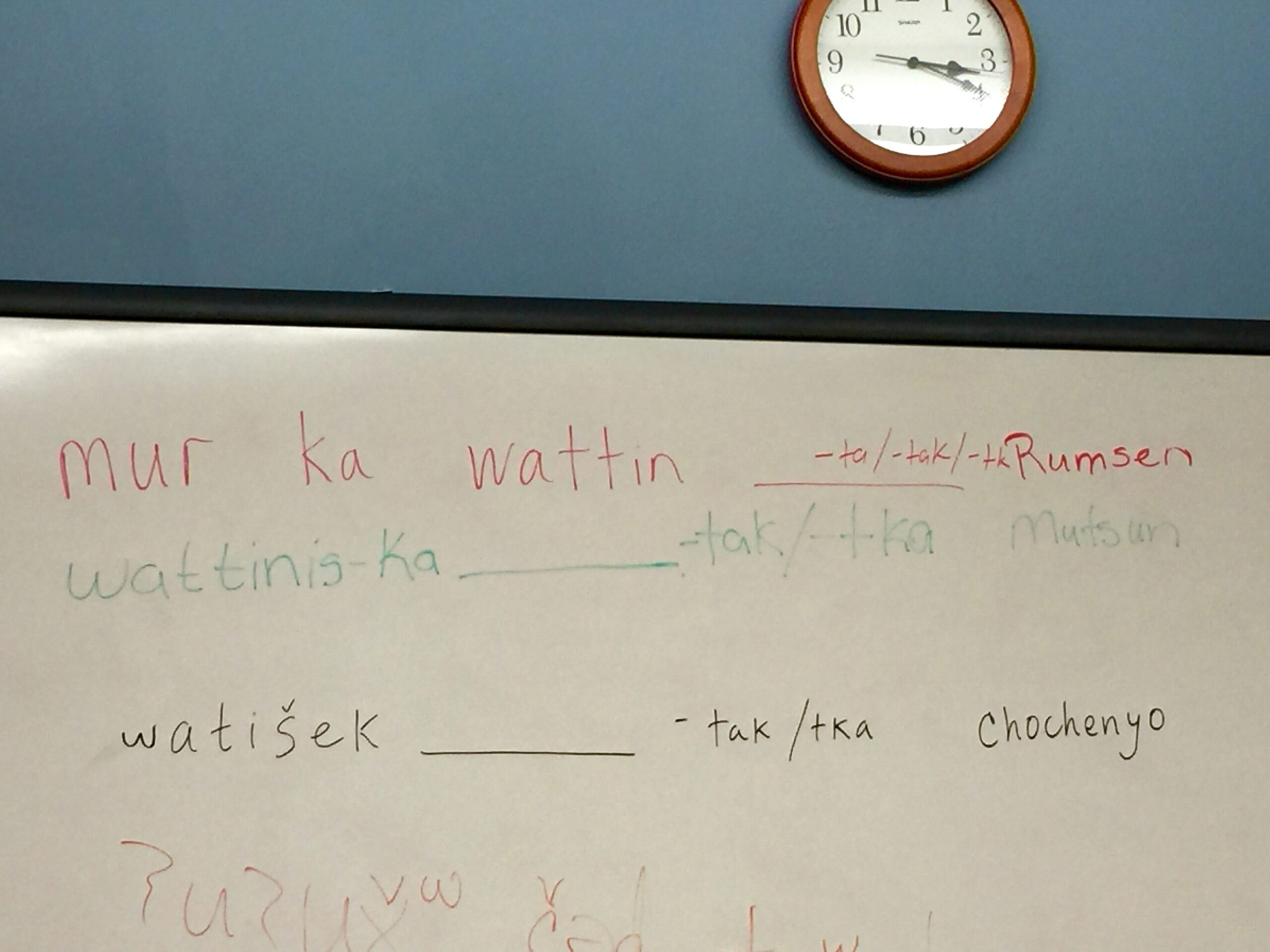

This year was special for so many reasons. My partner, Louis Trevino was working on his heritage language, Rumsen Ohlone, and we – along with Quirina Geary, Hope Casanero, and Rico Miranda – formed the first Ohlone comparative study group, with all four of us conversing in our respective languages of Chochenyo, Mutsun, and Rumsen. We worked to understand sound changes and realized our languages are much similar than we previously thought. With this inception, we surely will collaborate more to continue to make our Ohlone languages strong.

Another special part of this year’s Breath of Life was the ability to work with another Chochenyo person, my cousin Deja Gould. Deja is a special person to me, she has shown incredible love and dedication to our beautiful Chochenyo language, and has worked with me for a few years now on speaking and using our words, and teaching it to her young son, Kai. Deja and I are related, but we didn’t grow up together, and over the course of us working together, I’ve seen her passion and that gave me much comfort and trust in working together. Our project was to translate a story that was recorded in our family’s Sunol Rancheria in the 1920s. The story was told by two elder speakers who saved our language from extinction: Angela de los Colos and Jose Guzman. John Harringon recorded their words, and I am grateful for him, as well. Angela and Jose shared an epic story about bees defeating a person who harmed them, and it starts off waaka kiikne muwekma hooyo tappor, waaka herwekne ‘ayye yišša. waaka muuni yišša, ‘ayye huššištak waaka ‘itma ‘ayye ‘atkokne roote ṭuyetka. Literally: He told the people to gather wood, that he was to sweat and dance the last time. He started to dance, and in the morning he rose up and exploded into the wind.

This story hasn’t been told fully in Chochenyo in over 80 years, and was primarily in Spanish, with some English, and even less Chochenyo. Over the week, Deja and I worked to translate and, sometimes, coin new words we lacked in our attested documentation, such as aytakiš-pinnan (lady-bee) for queen bee, and kuwaaču-pinnan (bee sugar) for honey. We looked closely at our grammatical structure and nominalized verbs into nouns that will be able used in the future, even outside of this story. We even added a brand new song to this story. We know that traditionally our stories had song included in them, but none of our existing stories have that. By studying song patterns on one of our wax cylinder songs, we took a glimpse into the structure of a song, and changed all the words to be a haunting verse in this story, entirely sung: manni roote, manni roote? manni roote mak-šiininikma? manni roote mak-muwekma? Literally: Where are they, where are they? Where are our children? Where are our people? This was sung in the part of the story where the bee children and the bee adults go missing. Melissa Violet Leal (Esselen/Ohlone) sung this song for us, and we are grateful to have a piece of our story back.

This story’s translation reminded me of reinvention and change. Surely, this story is not told in exactly the same fashion as it was in the pre-contact times, in the old world before the Spanish and the Missions came. It is probably even different than when it was told in the Rancheria times of the 1920s and 1930s in Sunol. The story has changed, but we have too. We don’t dress, or speak, exactly as our ancestors did – but that does not mean we aren’t Indian. We have always found a way to reinvent ourselves, while keeping the core values of who we are. This story is an extension of that.

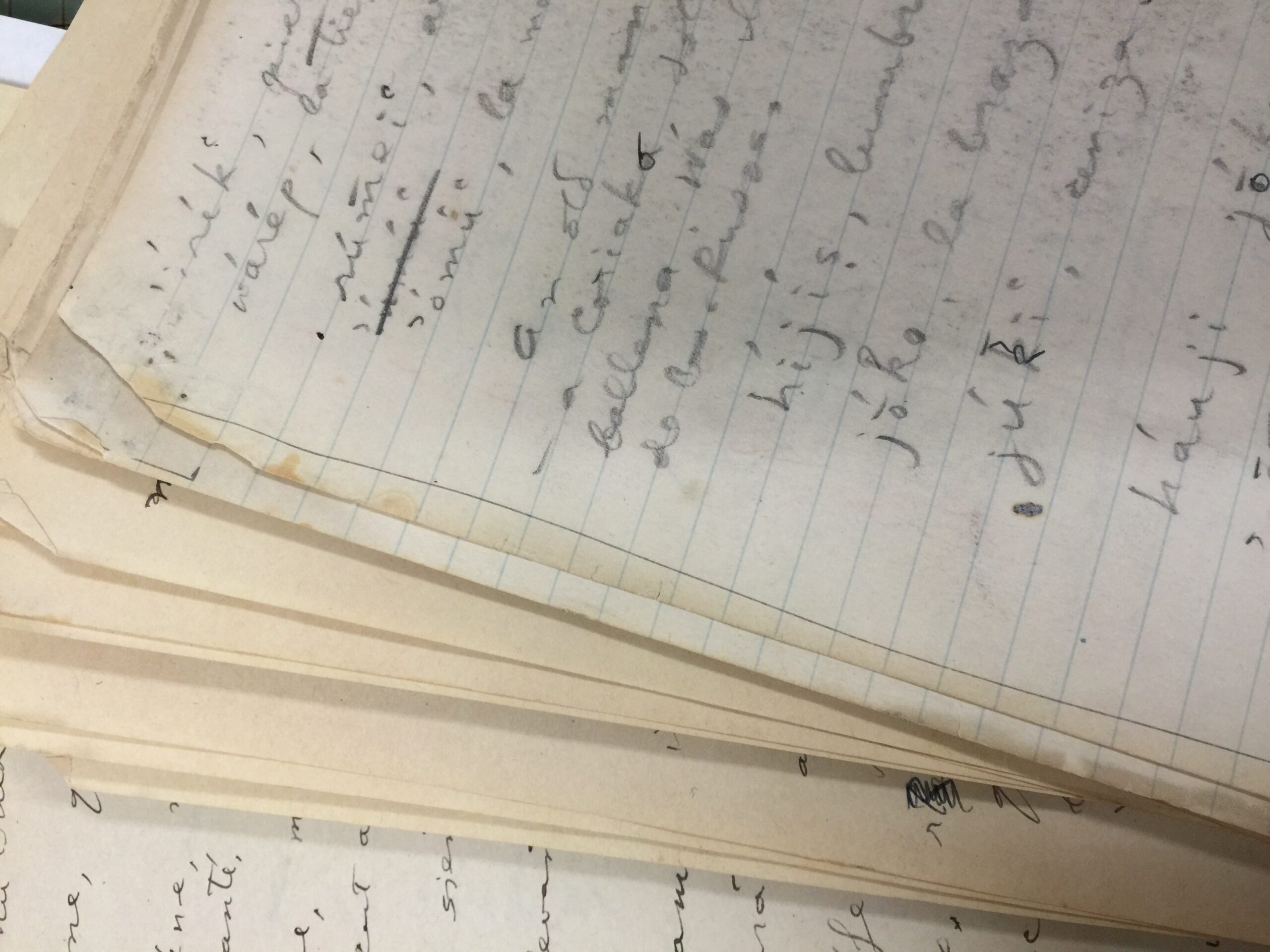

Early in the conference, Deja and I stumbled on the J.P. Harrington notes on the Chochenyo language that we have worked so closely with digitally, but have never touched or seen the physical papers. For me, was always assumed they were in Washington, D.C. As soon as we heard the papers were a few hundred feet from us, my heart dropped, and we nearly ran to them. It was the anticipation of seeing someone you love, that has been gone for a while; similar to the feeling when at the airport, and you’re waiting for a relative you love very much to come out of the gate. And we saw the notes, and we touched them with our bare hands – knowing those papers saved our language, knowing those papers touched the hands of our family. Now our hands collectively bond with the DNA of the words, the DNA of our ancestors. There is no separation.

I want to thank Deja, and all of those who have worked tirelessly to make this conference a success – especially Leanne Hinton, and Marina Drummer, who do so much to make the Advocates and Breath of Life happen, and happen successfully. I know as long as I am alive (which I hope will be long), I will be an advocate for Breath of Life. I see the power this program has, and the magic that comes out of this. Like the abalone necklace my friend repaired, our language will never be exactly the same as it was before the others came. Some parts might be missing, for now, but it can still be beautiful. Like us, our language can still thrive, the words can be renewed, and conversations and story can come home again. Guided by Angela and Jose, and all of our ancestors, we are seeing this done.

For more information on the Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival (AICLS) visit http://aicls.org/