Omesia Said…

Love, Sex, and Tenacious Survival

Written by Louis Trevino

‘ee, miššix mak ‘aa neeya.

muur mur, ka ‘oksey ukxakay rukkatiki ‘ečilat ‘is tuknutk. ‘arru ‘immey ‘utti rukkatiki xuyya, tannay mur ‘eeweki šiina mišyon. kuwee mur miššix. mur keččeš ša mišyon. tannay mur ‘eeweki šakay mirkanakay, ‘is ‘utti ‘aa pannan. ‘inn ‘exxe mur ‘utyey xekčošt ‘aa, ka ‘oksey ukxakay. ka ‘unnixin čiyya. ‘arra mak katyun makkey katta iṣmen, ‘ee. ‘inn paču mak pusyep makkey katta iṣmen ‘attap. miššix mak ‘aa neeya. ‘arra mak čulleki. ‘ee, miššix mak ‘aa neeya.

In the past, my ancestors lived in Echilat and Tucutnut. Back then they all lived there, then came the Mission. It was not good. The Mission was bad. Then came the Americans, and they were even worse. But they were very strong, my ancestors. They allow me to be here. Like the moon, we waned, yes. But also like the moon, we have revived. We are well now. We have returned after a long absence. Yes, we are well now.

“In Indian times there was no such thing as bad years.” (Harrington Reel 80, Page 372)

The Carmel Mission drew in 1062 Rumsen people while in operation, beginning in 1770. By 1778, the Rumsen villages of the lower Carmel Valley were completely absorbed into the mission. The first of my own ancestors to appear in the records of the Carmel Mission was baptized in 1775. He was brought from the village called Echilat, truly ‘ičilta – the place of the climb. He was given the name Simeon Francisco by Junípero Serra, who also baptized his wife, son, and six daughters. In 1795, the population at Carmel Mission peaked at 876 Indians; this included all of the Rumsen people, and a portion of the Esselen people. At secularization of the Carmel Mission in 1834, there were just 140 Rumsen people remaining.

The ineffable harm done to the Rumsen people by the mission system is not an uncommon narrative among California Indian communities that fell into its grasp. Those proselytizers, those germ-carrying colonizers, along with their military compatriots, established a new social order – one in which their ways and beliefs were poised as superior to ours. This new social order was a fiction they imposed upon us. The dystopia they founded led to the loss of so much for Rumsen people; specifics about spiritual practices, dances, facial tattoos, clothing and adornments. Some of these specifics will forever remain questions in the minds of modern Rumsen people; something will always be missing, because of Serra and his institution.

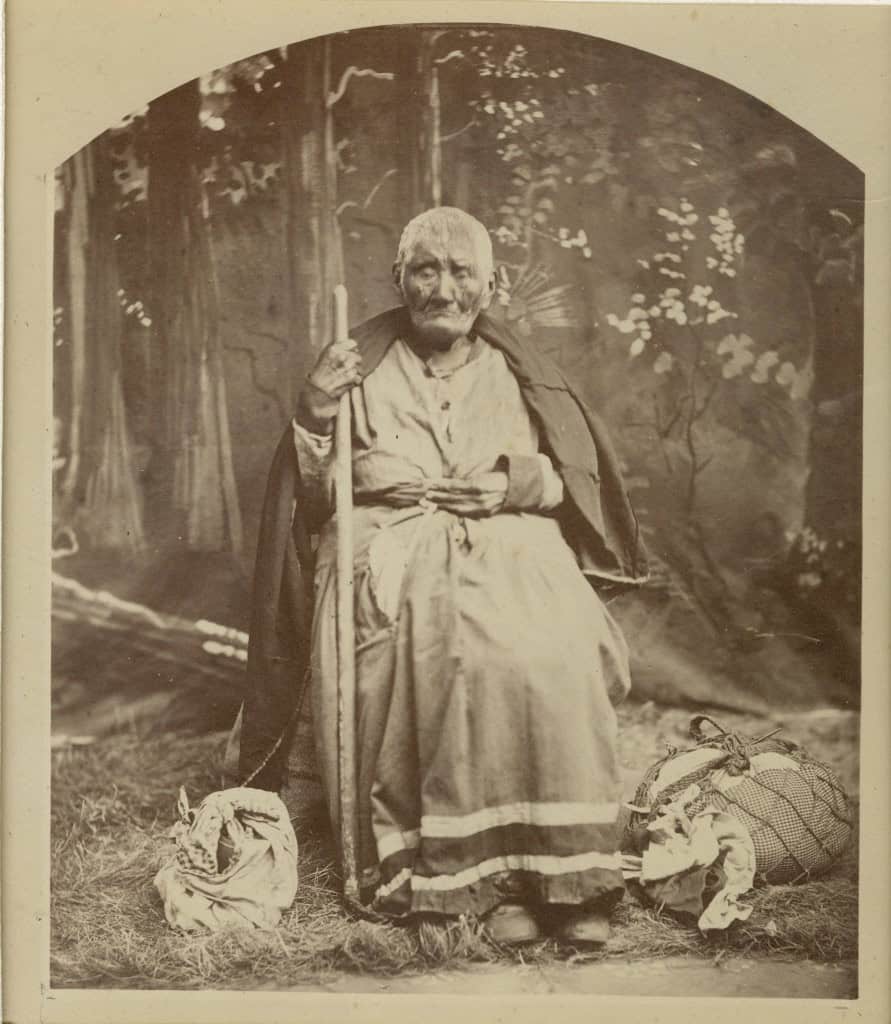

Yet the narrative of Rumsen history is far from being solely about loss; for much was saved, thanks to those Rumsen people who carried in their memory the old ways, and who continued to live them after the mission had been secularized. One such woman was Neomesia Teyoc, always referred to as Omesia, or simply “la vieja.” Omesia was born in 1791 in the mission, to two parents brought from the village Kallendaruc, literally “at the sea village.” She appears in the baptismal registry as baptism number 1551. Her life overlaps the time of the village, some seventeen years before the Mission San Carlos considered their “conquista” completed, that of the mission, and that of secularization and dispossession; in other words, she witnessed and endured the blunt force of her people’s colonization by the Spanish, the Mexicans, and the Americans. Omesia was among those 140 Rumsen people remaining at the end of the mission period, along with my ancestors. She is the archetypal mission survivor: she would never live the same life as her elders, but she did hold on to her identity and her language with tenacity.

“It was Omesia that Isabel got to hear talk most.” (Harrington Reel 80, Page 353)

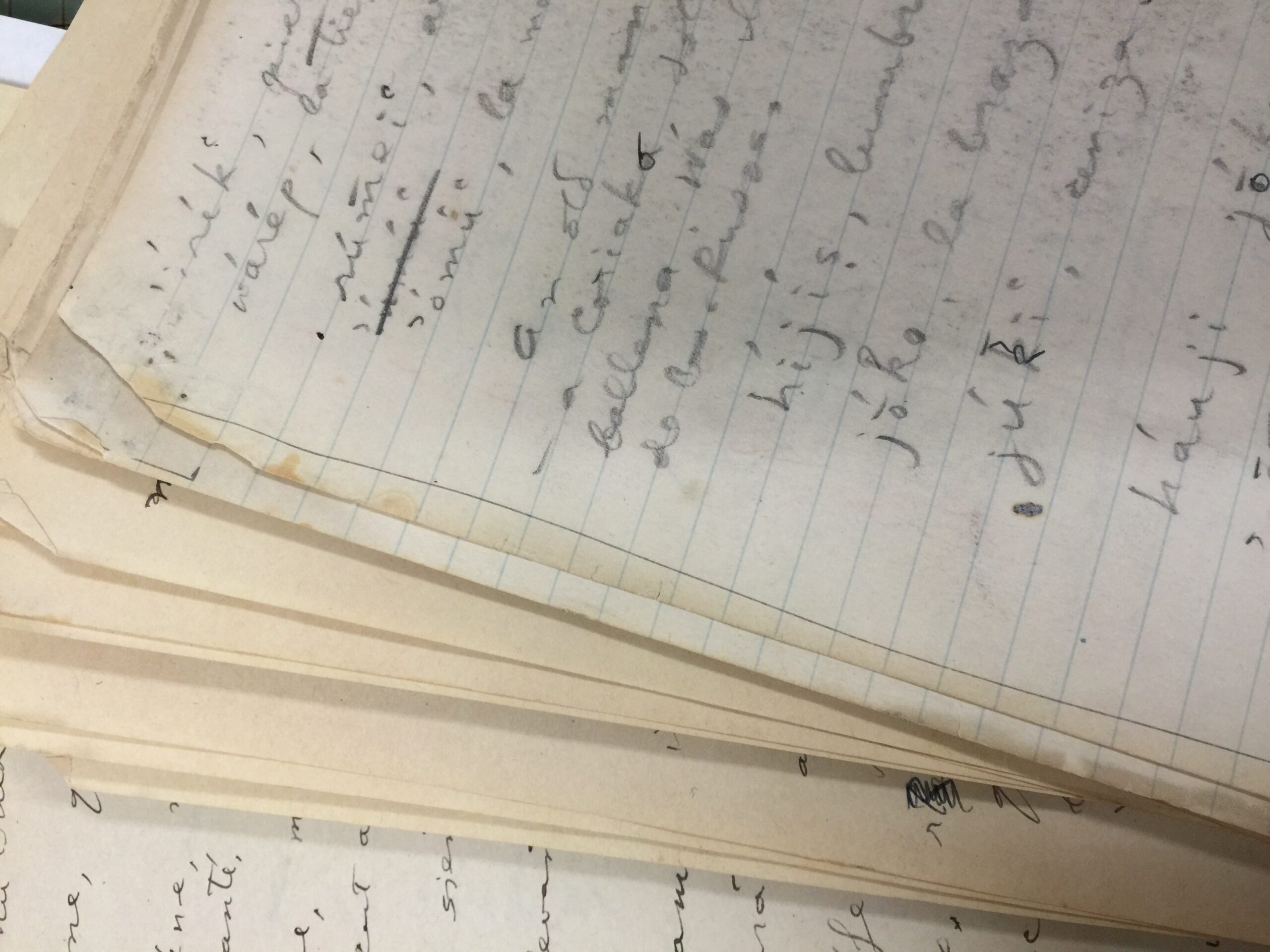

Omesia passed away in 1883, but not without ensuring that her knowledge and experiences were shared with another generation of Rumsen people. Through Isabel Meadows, the last native speaker of Rumsen who passed away in 1939, Omesia’s knowledge and experiences were preserved in the notes of John Peabody Harrington. Isabel, who Omesia called šappela, would spend the last ten years of her long life working to extensively record the language and stories of the people of Carmel. A frequently repeated phrase is “Omesia decia…,” or, “Omesia said…” The documentation ranges from the mundane to the extraordinary, from the heartbreaking to the humorous, and from the painful to the uplifting. Among those tens of thousands of pages are saved gems about love among the Rumsen people. Family, community, and intimate love are all represented in the Rumsen language documentation.

Even in her own appearance Omesia reflected the pain and beauty of her life. Within the Harrington notes there are some detailed descriptions, seemingly dissonant images of this incredible woman’s countenance. In one, Isabel describes fleas “just swarming on her collar, and [she would] reach and catch one of them and crack it between her teeth (katt, to bite a flea, head louse, or body louse)” (Harrington 62: 22). This passage comes when Harrington elicits the word raax, louse, from Isabel. Omesia lived along the bank of the Carmel River in great poverty. She once lived nearer to the Mission in Carmel with a small community, but the sadness that came to them when they remembered all the people who were there caused Omesia and other old women to move away from there (Harrington 61: 881). Another description of Omesia’s appearance comes from the elicitation of ‘umšiliwx, a beautiful red flower that grew after the first rain of springtime in the Carmel Valley. She would always wear ‘umšiliwx in her hair, or in the large holes in her ears through which, as Isabel describes, “the Indians had anciently worn tufts of quail feathers” (Harrington 62: 112), a detail she would have learned from Omesia. These emotionally provocative images give some impression of the depth of Omesia’s complexity, of her suffering and the beauty of her survival. This same depth and nuance reveals itself in the language documentation.

The citations that begin with “Omesia said…” are generally the most trusted in the notes, because they are the words that Isabel remembers directly from Omesia’s lips. Omesia’s authority comes from her connection to that world before they came, from the strength of her memory, and the stubbornness with which she carried it all. From Omesia we have ka-miččiys – literally “my bird nest” – used by a mother to call her son with affection. We also have, tirrise karmentay rukk – “I am happy for the people of Carmel” – to which Isabel adds, “she would say this when she heard something bad had happened to people she did not like” (Harrington 66: 556). We also have from Omesia, saar, saar! – Pray, pray! “Omesia said this when she saw the crondas [cronies, patrolmen] and Juana Cota [the wife of Manuel Boronda, whose father accompanied Junipero Serra to Monterey, and who became a landholder following secularization of the Carmel Mission] passing below the mission in her cart, harassing them, on [their] way from their home at Los Laureles [to the Mission]” (Harrington 65: 488). One can imagine the angry sarcasm of that utterance, urging this colonial beneficiary to participate in the institution that disempowered Omesia’s own people to their perverse benefit.

“Old Tom Breyli (phon.) used to make a pun on Omesia’s name and instead of saying la vieja Omesia said la vieja mecha – wild girl.” (Harrington Reel 61, Page 979)

The range of language document reveals Omesia’s personality and lifestyle. From her humor, to her anger, to her pursuit of physical pleasure. Omesia’s sexual liberation and sense of humor frequently reveal themselves in the language documentation. Omesia is a woman uncensored and unabashed.

Among the phrases Omesia said:

šokšost, big-testicled one (Harrington 65: 573)

‘iṣṣak wa-pilliw, his penis is big (Harrington 65: 563)

piina ša waaten kuuwe rottey wa-pilliw – this one who goes here has no penis (Harrington: Impt. sentence) (Harrington 65: 563)

‘ičče makk kulyarin, let’s go have sex (Harrington 65: 563)

mmmmmm, miššix wa-pilliw, mmmmmm, his penis is good (Harrington 65: 952)

pilwiṣt, chilón, one that has a big penis. Omesia said this when the men did not pay attention to her (Harrington 65: 563, 952; Harrington 66: 311)

Isabel learned each of these expressions from Omesia, and sometimes they would get her into some trouble. On one page of the notes Isabel describes a time her mother punished her for repeating one of the more explicit phrases she learned from Omesia. Isabel tells Harrington, “Omesia decia: kaṣ ṣummit ‘e-pilliw, [give me your penis]. Isabel went around saying kaṣ ṣummit ‘e-pilliw all the time, and Loreta [Isabel’s mother] heard her and said: You won’t go there with la vieja, hearing those words! She slapped Isabel and left her there crying. pilwiṣt, chilon [one with a big penis]” (Harrington 61: 744). Clearly, to Isabel’s mother, Omesia was a bad influence.

Yet Omesia is not always overtly sexual or profane in her words. Through Isabel she also preserved the full spectrum of Rumsen phrases of affection, applying from pets, family, and friends, to a spouse or partner.

ka meṣ ‘iwsen, I desire you.

ka meṣ muyšin, I love you.

ka meṣ polšonin, I have become crazy with love for you.

ka meṣ lomyonin, I have become completely, crazily in love (or sex-crazed) for you.

ka mačnanin, I have turned into Coyote. This is said when “you just lose yourself oblivious to the world,” and when a man “is wagging his tail for a woman.”

Again we see Omesia’s complexity shining through in the documentation. Having endured life in the Mission – under the Catholic gaze – she has refused to let go of Rumsen conceptions of love.

Among the most personally heartwarming notes in the documentation are xaayeno songs, songs sung by Rumsen women for the safe return of their love. Two were recorded on wax cylinders in 1902, but there were many such songs. Omesia’s xaayeno song is recorded only in the written documentation; Isabel says that Omesia taught her to sing this song to cause a boyfriend to return home.

Omesia’s song:

xaṣwaki ku wa-ṣirre, xaaye, xaaye, xaayeno.

Literally: His heart be scratched, come home.

Her Spanish description: Would that his heart be disquieted, so that he returns home.

As I study the documentation, I see a nuanced and multi-faceted depiction of my Rumsen ancestors, one that gives me great pride in the grace and tenacity with which those before me endured the worst times of our history. When I stitch together in my mind the descriptions of Omesia with the words from her mouth – the wisdom, the pain, and the love that come from her – I imagine my own direct ancestors, who must have known her, surviving with the same stubborn strategies. In that way, Omesia’s presence and voice makes my connection to my ancestors stronger; their voices and words are recorded nowhere, but she is my bridge to their experiences and perspectives.

Once, when I was telling stories about Omesia and the things she said around the dinner table, a friend asked me how old Omesia was and where she lived. I realized then that I was referring to Omesia mostly in the present tense, with great familiarity. I realized that, as I take the time to study the documentation for grammar or syntax, the things “Omesia said” are becoming a part of my own experience as a Rumsen individual. In some way, Omesia is guiding my work to contribute to the revitalization of the Rumsen language, and my development as a Rumsen man, unashamed and unabashed.

šuururu karmenta rukk,

šuururu Omesia.